The theme of this week is Agile development practice.

In my research, I sought to better understand the core principles that underpin Agile and consider which parts I could apply to my own practice, with a view to support my goal of: Understanding the theory and practice of making great games

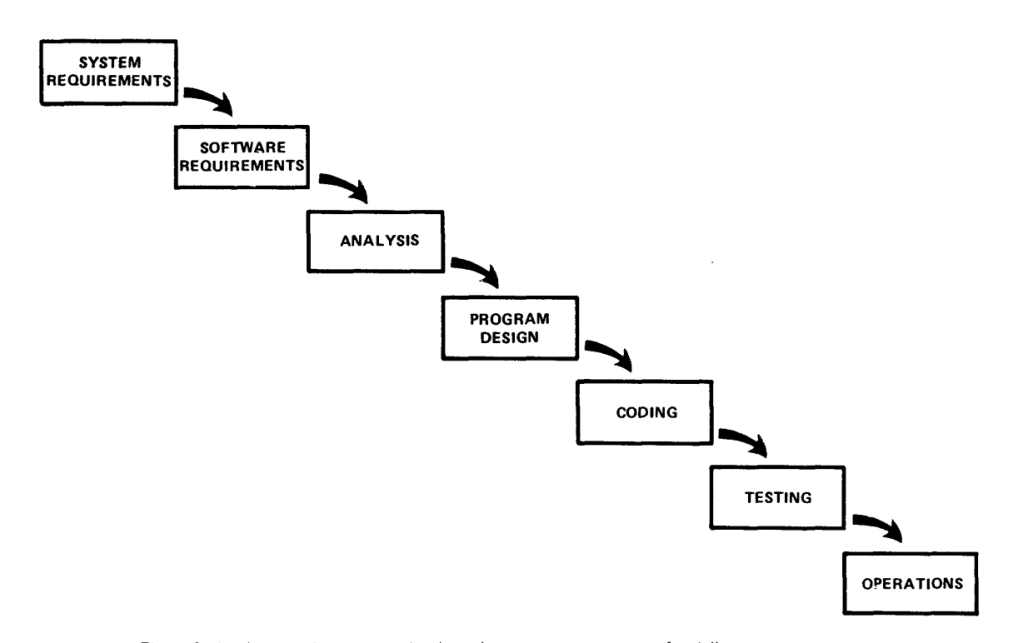

Agile is a topic that I have some experience with in my professional life, but have never studied as a framework, so I was interested to understand how closely my experience reflected the theory. I also explored the Waterfall methodology (Royce 1970) in comparison to Agile. To this end, I have looked at the various Agile approaches with a critical eye as I seek to develop my own.

Agile seems to attract avid fans, and undoubtedly there is considerable value in the approach. Some have even gone so far as to provide evidence that working in Agile makes people happier (Waldock 2015) although I view this with some skepticism. With the same passion that these fans have for Agile, there seems to be an equally passionate rejection of the traditional project management approach, Waterfall.

Agile Practices

Agile is the practice of repeatedly producing increments of standalone functionality, that are iteratively tested and improved upon over a series of sprints.

It is founded on a set of values that were created in 2001 by a group of Agile practitioners led by Kent Beck in a discussion about the future of software development:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The Agile manifesto does not describe itself as oppositional:

‘while there is a value of the items on the left, we value the items on the right more’

(Beck et al 2001)

However, this foundational set of values does create a feeling of opposition in Agile versus traditional development methods.

It leans heavily on the success of principles developed through ‘Lean’ manufacturing and integrating those principles into software development. For example, mapping key types of waste against those found in manufacturing in order to see and eliminate it (Poppendick 2001). Reviewing existing successful work in order to build on it in this way is exactly what i hope to achieve over the course of my study.

Over time, the various proponents of Agile have branched the core values into a range of disciplines and methodologies that now fall under the banner including Scrum, Extreme Programming (XP), Kanban, Feature-Driven Development, Lean, Agile Modeling and Dynamic Systems Development Method, to name only a few. (Shankarmani et al 2012).

Envisioning

In Essential Scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process, author Keneth Rubin gives an overview of the Agile product planning process: ‘Envisioning’ It entails distillation of an idea into a clear vision and then planning of its execution. Outputs of such product planning activities include:

Product Vision: Explanation of the idea in a single concise paragraph.

Product Backlog: A prioritised list of Product Backlog Items (PBI) required to meet the product owner’s vision. Sometimes also referred to as Tasks or Value Drivers.

Product Roadmap: A target set of releases for our product

Other Artefacts: Anything else that may be required to complete the process such as market research, business case development or a confidence threshold – an envisioning ‘definition of done’. (2012)

I found the tools and frameworks in this segment really valuable and have already started implementing them. This week at work I had to create a scope document to pitch an automated report. I applied some of Rubin’s envisioning activities including creating a product vision, defining a target customer, describing the key benefits and purpose of the project and proposed roles and responsibilities. Using these frameworks meant that I was able to really clearly communicate my needs and the outputs were very well received by the developer I was working with. I will definitely use an envisioning framework again.

Agile Estimation

The time estimation process consists of 3 key questions:

- How many features will be completed?

- When will they be done?

- How much will this cost?

When we are estimating, a fundamental is the focus on accuracy, rather than precision – and we should do it as quickly as possible. Planning does not actually deliver value in and of itself and so the amount of time we put into doing so should be relative to the return. When planning my time and projects I will consider – what is the benefit of the level of precision I am working to achieve? Other useful principles that I will be integrating into my practice include speed over accuracy, collaborative techniques and relative units (Berteig 2015).

While the intention and values behind the process of Agile estimation are valuable, I found some of the methodologies such as Story Points, Fibonacci and Complexity Buckets too complex for my needs. Ideal Days are more straightforward but again, seem a little convoluted as an approach when you’re short on time.

Whilst I see value in measuring velocity for diagnostic and planning purposes (Rubin 2012) I can see this having most value in large projects. It would be difficult to get a good return on the time investment of going through the process with a smaller project – unless implemented in a much lighter-touch way.

I will aim to apply these techniques in a way bespoke to the needs of my next project – perhaps breaking them into simple Pomodoros for a piece of solo work.

Agile v Waterfall

Given part of the argument of moving away from Waterfall lies in its lack of flexibility, valuing ‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ (Beck et al, 2001) I was surprised by the number of process tools that fell under the banner of Agile and how these ranged from prescriptive to adaptive. Rational Unified Process for instance, contains over 120 points of process, while Kanban has only 3. (Shankarmani et al 2012).

In this way, I see some conflict between adopting Agile as a set of processes and as a mindset which governs your approach but is more flexible in nature. I am naturally more drawn to flexible frameworks, especially in creative endeavours. If you are truly innovating in some way your development framework should not be rigid. Creativity is inherently disruptive and generative environments require a culture of listening and making room for play (Schmidt Campbell, 2021).

From a business perspective, I understand the need for predictability and scalability of approach, but rigidity on process seems oppositional to the core Agile principles and a potential blocker to innovation.

Another potential challenge I saw in Agile and in particular, Scrum when I consider it in comparison to Waterfall is in the argument that it improves your return on investment by reducing costs: ‘the waste elimination that we’re able to bring to bear by skipping work that is not essential to our minimum viable product makes for a faster, leaner, and more cost-effective development team — and a healthier bottom line.’ (Rubin 2013). If I am a contractor delivering a project that is less concrete in scope and responds to changing needs, can I know the cost and contain it? Does it then make it more challenging to define an end point where the project is done? The concept of scope creep is a well-known one, with countless articles available on strategies for how to manage and prevent it.

I have found aspects of a Waterfall approach extremely useful when developing a complex product. When you have cross-discipline teams attempting to produce a testable product every cycle iteration, understanding dependencies and the order of requirements is critical (Keith, 2010). It is virtually impossible for each team to work on tasks entirely independently and in silo. I have experienced this first hand in my work developing learning technology products in my role as Head of Education at MakerClub. There, although we worked in short sprints, we approached each one almost as a mini project and worked out the order of dependencies required in order to ensure no one became blocked.

That being said, the benefits of Agile are well documented and researched. High-agility businesses across industries generally grow faster and are more profitable where the are concepts are applied consistently (Aghina et al 2020, Inman et al 2010).

When applying the values of Agile in a games development context, it is important to create a culture of open communication where individuals are empowered to take ownership. In terms of leadership, I ascribe to an adaptive framework and servant philosophy, which calls for ‘a diagnostic mindset on a changing reality’ (Heiftz et al, 2002:73) simplicity and adaptability alongside team enablement and facilitation (Sinek, 2014) and so this communication culture really spoke to me.

Key learnings and Takeaways

There were definitely takeaways that I have already started adopting into my own work.

Good envisioning informs your whole practice

Having a framework for describing the needs and purpose of my project creates clarity from the off. I have already seen value from applying this learning and will continue to do so.

Chunking up your work ahead of time helps you get it done on time

Planning and reviewing my work in time blocks will help me understand my progress and velocity. I will assess the likely return on this time investment and select an approach in line with the needs of my project.

Agile is great, but a blended approach is most powerful

Learning more about Agile has helped me consider how I want to approach my own development practice and I have already utilised tools like sprints, Kanban boards, User Personae and Product Backlog. However I won’t discard the learnings and success of more traditional development methodologies such as Waterfall. Finding a way through a project while tackling challenges such as being open to change while preventing project failure through repeated requirement change are best tackled with learnings gained from both schools of thought (Glass 2001).

References:

AGHINA, Wouter, Christopher HANDSCOMB, Jesper LUDOLPH, Dániel RÓNA, and Dave WEST. 2020. ‘Enterprise agility: Buzz or business impact?’ McKinsey [online]. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/enterprise-agility-buzz-or-business-impact. [Accessed 24th December 2021].

BECK, Kent, Mike BEEDLE, Arie van BENNEKUM, Alistair COCKBURN, Ward CUNNINGHAM, Martin FOWLER, James GRENNING, Jim HIGHSMITH, Andrew HUNT, Ron JEFFRIES, Jon KERN, Brian MARICK. Robert C. MARTIN, Steve MELLOR, Ken SCHWARBER, Jeff SUTHERLAND, Dave THOMAS. 2001. Manifesto for Agile Software Development. [online] Agilemanifesto.org. Available at: http://www.agilemanifesto.org/ [Accessed 20th November 2021]

BERTEIG, Mishkin. 2015. ‘Agile Planning in a Nutshell’. Agile Advice [online]. Available at: http://www.agileadvice.com/2016/08/30/agilemanagement/agile-advice-start-executing-little-planning/ [Accessed 18th December 2021]

GLASS, Robert. 2001. ‘Agile v Traditional: Make Love, Not War!’ Cutter IT Journal. 14 (12) 12-18. [online]. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/view [accessed 18th December 2021]

HEIFETZ, Ronald A and Martin LINSKY. 2002. Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive Through the Dangers of Leading. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

INMAN, Anthony, Samuel SALE, Kenneth GREEN and Dwayne WHITTEN 2010. ‘Agile

manufacturing: Relation to JIT, operational performance and firm performance.’ Journal

of Operations Management. 29(4) 343-355 [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.06.001 [accessed 18th December 2021]

KEITH, Clinton. 2010. Agile Game Development with Scrum. New York: Pearson Education

POPPENDICK, Mary and Tom POPPENDICK. 2003. Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit. New York: Pearson Education.

ROYCE, Winston. 1970. ‘Managing the Development of Large Software Systems’ in Technical Papers of Western Electronic Show and Convention (WesCon). 1-9, August 25-28 1970 Los Angeles: USA.

RUBIN, Kenneth 2012. Essential Scrum : A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process. Addison-Wesley.

RUBIN, Kenneth. 2013. ‘3 Big Benefits of Scrum and Why It Beats Waterfall for Product Development’. OpenView Partners Blog [online]. Available at: https://openviewpartners.com/blog/3-benefits-of-scrum-beats-waterfall/#.YaJhLZDP3DI [accessed 11th November 2021].

SCHMIDT CAMPBELL, Mary. 2021. ‘Unity 2030′[introductory address]. Employee conference.

SHANKARMANI, Radha, Renuka PAWAR, Shankar. MANTHA and Vinaya BABU. 2012. ‘Agile Methodology Adoption: Benefits and Constraints.’ in International Journal of Computer Applications: Foundation of Computer Science 58(15) 31-37

SINEK, Simon. 2014. Leaders Eat Last. New York: Penguin.

WALDOCK, Belinda. 2015. Being Agile in Business – Discover Faster, Smarter, Leaner Ways to Work. New York: Pearson Education.

ZELCOWITZ, Marvin. V. 2004. An Introduction to Agile Methods in ‘Advances in Computers‘ 62(1). 2-63. San Diego: USA. Elsevier.

Full list of figures

Figure 1: Mary POPPENDICK and Tom POPPENDICK. 2003. The Seven Wastes. From: Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit, pp.4

Figure 2: Radha SHANKARMANI, Renuka PAWAR, S. MANTHA and S. BABU. 2012. Prescriptive vs Adaptive Scale. From: ‘Agile Methodology Adoption: Benefits and Constraints.’

Figure 3: Winston ROYCE. Implementation steps to develop a large computer program for delivery to a customer. From: Managing the Development of Large Software Systems, pp.2

You must be logged in to post a comment.