The concept of Communities of Practice was first developed as a social learning theory by a working group at the Institute for Research on Learning (IRL), reviewing the development of learning of apprentices during their Apprenticeships. It was observed that learning interactions were more frequent between apprentices and their peers, than the apprentice and the master.

The term ‘Communities of Practice’ was coined to describe these self-organising learning communities and then first published as a concept by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger-Trayner (formerly Wenger) in ‘Situated Learning Legitimate Peripheral Participation’ (1991). Since then as a term it has developed meaning as both a ‘conceptual lens through which to examine the situated social construction of meaning’ (Cox 2005: 1) and a description for ‘a virtual community or informal group sponsored by an organization to facilitate knowledge sharing or learning’ (Cox 2005: 1). However, it is the latter which I will use in this context, in order to consider how it applies to both my professional and academic work.

Communities of Practice (CoP) are defined as ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’ (Wenger-Trayner 2015: 1).

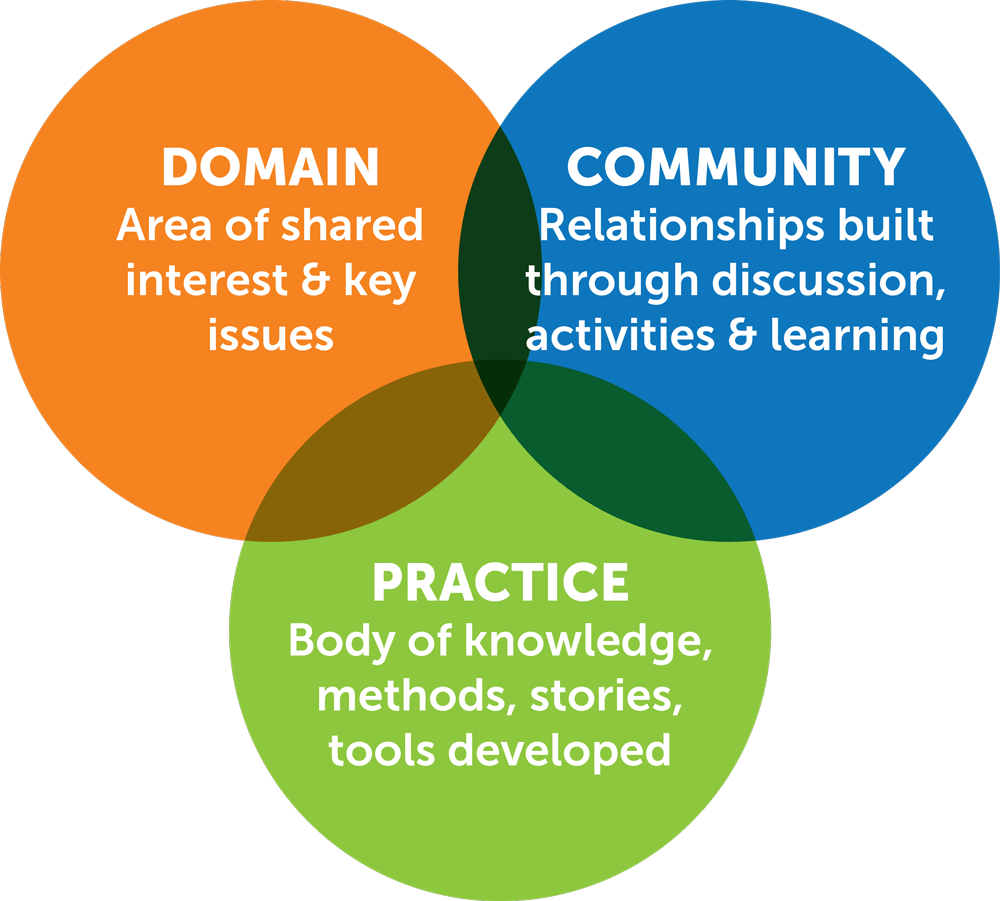

In this definition, CoP are comprised of 3 main elements, all of which must be present in order to meet the criteria:

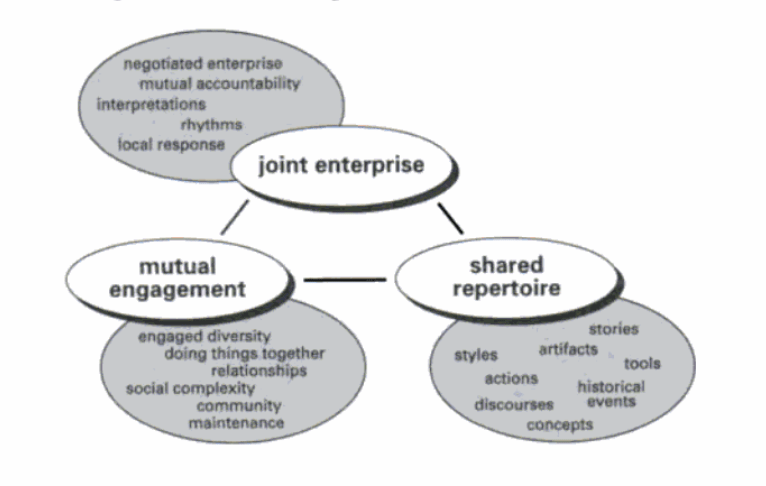

The community then align on a model of competence for the practice of their domain, defined through mutual engagement, a joint enterprise and a shared repertoire (Wenger-Trayner 1999: 73).

For instance, in this way you might find a CoP in a games studio where you have a team of developers, working on a title together, who over time, negotiate best practices for their Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC).

As well as defining competence, the community will help accelerate the learning of its members and the advancement of the practice. In organisations, a CoP is claimed to also accelerate professional development, break down organisational silos and build stronger, happier teams (Webber 2016).

As a result of my first phase of research, I realised that I was using elements of a CoP such as peer learning and sharing of practice on a regular basis to define competence and accelerate learning within my own team at work. When thinking about how I might apply the concepts involved to further improve this, I decided to introduce a weekly discussion topic to prompt further discussion and debate about our practice.

After some further research, I considered whether a CoP may really be formed in a workplace; where roles are clearly defined and set out for the group who practice it in line with the needs of the business. In many organisations, decisions about how a practice should be carried out and what constitutes good are made in a hierarchical manner; my idea was one of them.

It led me to the question; in a work setting, can a community ever really own it’s practice and meet the definition criteria, or is Wenger-Trayner’s framework an idealised one that doesn’t apply in professional practice? My thinking is likely no, particularly with the rise of hyperspecialisation in the technology industries:

‘Work previously done by one person is divided into more-specialized pieces done by multiple people, achieving improvements in quality, speed, and cost.

(Johns et al 2011)

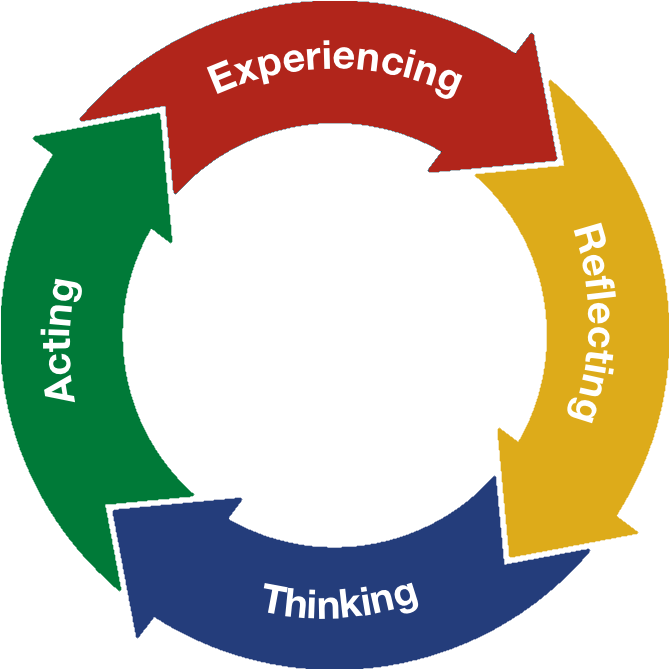

Where outcomes are more tightly managed, a rigidly defined CoP framework may be less applicable as workers are less likely to be able to define their own goals and success measures (Cox 2005). Nonetheless, I see significant value in the concept and applications. I already have strong views about the value of project-based learning and the ‘transformation of experience’ (Kolb, 1984: 2) from my time working in education at MakerClub, so it was interesting to hear about these theories tie into into CoP theory.

As meaning is central to human learning it is also inherently tied to human practice (Wenger-Trayner 2014). In a CoP, engaging in the practice is what gives it meaning, and the practice itself is the property of the community. It occured to me that Kolb’s model reflects the model of Communities of Practice as a cycle of practice, reflection, sharing and learning.

It was also interesting to reflect on this in the context of my course progress so far. Initially, I attempted some learning on programming using the Code Academy platform as it is so widely known. However, I was working alone and as the code was not taught in context – and therefore meaning was suspended (Wenger-Trayner 2014) – it was difficult for me engage with the content and retain information. In comparison, I made the greatest progress in my technical learning during the Rapid Ideation weeks, where I was learning in context and discussing my progress with my peers and mentor.

As I learned during my research on critical reflection and the creation on knowledge, learning, knowledge and power are always in interaction. In particular, the theories of post-modernism and deconstructionism v modernism and critical social theory (Fook and Gardner 2007). Therefore who leads a CoP and which ones define the practice are also interesting questions. If the body of knowledge of a profession is defined by the most prominent group of people that engage with the practice and each other, then this creates an interesting power dynamic and raises questions for me about who might benefit depending on the knowledge and stories that are shared or how the best methods and tools are defined. I can imagine scenarios where what starts as a CoP could become a powerful and exclusive club, creating knowledge based on its own rules and rejecting challenge, or alternatively where a group appropriates an activity and declares themselves the authority on competence.

For instance, I started considering how this applies to my professional and academic practice; where I may already be a part of a community of practice or how I might seek to join one. There are many conferences such as the Games Developer Conference (GDC) or Gamescom which serve as opportunities for different CoP within the games industry to share the newest knowledge, methods stories and tools (Wenger-Trayner 2015). Developer Relations is a relatively new but growing disciple, so I was surprised and excited to find that in 2021 a second annual conference ‘DevRelCon’ had happened in November and an online community existed, run by an organisation called DevRel.

‘A place for learning and sharing about developer relations, community, marketing, and experience.’

(DevRel 2021)

On a closer read, I realised that DevRel was a Developer Relations consultancy firm. There is an inherent conflict here, with a potential financial stake in what is defined as “good”.

In this way, a CoP isn’t always good and uniformity or agreement isn’t necessarily a sign of a successful community. In fact, homogenisation is usually a sign that learning in the community has stalled. A true CoP should be open to challenge; where members engage in a practice that is constantly negotiated (Wegner-Trayner 2014).

On a similar train of thought, I reflected back as to why I would like to set up some more opportunities for my team to engage in conversations about defining competence and best methods. Is it for reasons of empowerment? Or rather, a new duplicitous way of exercising normative control (Cox 2005). When I think deeply into my motives, really it is both. I want the team to be the best they can be within the scope of their role. Does the motive matter if the outcome benefits everyone, including me? Reflecting back to my research on ethical theory, perhaps I should take a more consequentialist ethical perspective in that if the outcomes are positive for all involved then the motive doesn’t matter and should not be viewed with negative connotations (Kara, 2017). However after some more thought I came to the realisation that by not opening up the conversation beyond the scope of the current role we may miss opportunities for innovation.

Ultimately, it is important to view the creation of all knowledge with a critical lens when there is a power dynamic at play. As with Agile and other frameworks we have reviewed, my conclusion is that I will take the Communities of Practice methods that I find inspiring and use them according to the situation I find myself in, as opposed to be bound by the rules as others see them. As I progress through the course and my career, participating in games industry communities that may have defined a set of competencies around a practice, I will be sure to critique them and not ignore my own ideas and experience. I will also continue to reflect on and critique my own decisions in the communities where I have influence, ensuring I remain open to the critique of others.

References:

COX, Andrew. 2005. ‘What are communities of practice? A comparative review of four seminal works.’ Journal of Information Science 31:6 2005. 527-540 Lean Library.

DEVREL. 2021. ‘2021 DevRelCon’. DevRel [online]. Available at: https://developerrelations.com/event/devrelcon-2021 [Accessed 2nd January 2021].

FOOK, Jan and Fiona GARDNER. 2007. Practising Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

JOHNS, Tammy, Robert LAUBACHER and Thomas MALONE. 2011. ‘The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization’. Harvard Business Review 89:7 56-65. Harvard Business Publishing.

KARA, Helen. 2017. Research Ethics (Ethical Theories) [National Centre for Research Methods]. Youtube [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyF8UzDMNsw %5Baccessed 2nd January 2022]

LAVE, Jean and Etienne WENGER-TRAYNER. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

WEBBER, Emily. 2016. Building Successful Communities of Practice. Tacit.

WENGER-TRAYNER Etienne and Beverly, WENGER-TRAYNER. 2015. Communities of Practice, a brief introduction. Wenger-Trayner [online]. https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf. [Accessed 2nd January 2022].

WENGER-TRAYNER Etienne. UDOL Academic Conference 2014 – Communities of Practice: Theories and Current Thinking. Youtube [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71xF7HTEipo [Accessed 2nd January 2022].

WENGER-TRAYNER, Etienne. 1999. Communities of Practice Learning Meaning and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Full list of figures

Figure 1. Etienne WENGER-TRAYNER and Beverly, WENGER-TRAYNER. The Three Characteristics of a Community of Practice. From: Communities of Practice, a brief introduction. Wenger-Trayner [online]. https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf. [Accessed 2nd January 2022].

Figure 2. Etienne WENGER-TRAYNER. 1999. Dimensions of Practice as the property of a community. From: Communities of Practice Learning Meaning and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Figure 3. David KOLB. Model of Experiential Learning. Experiential Learning Institute [online]. Available at: https://experientiallearninginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IFEL-Learning-Cycle3.png [Accessed 2nd January 2022].

You must be logged in to post a comment.