To meet my own goals this week, I have decided to focus my research on understanding the role of user testing in games, explore my own perspectives on ethics in research and consider what the future of user research may look like.

I started by researching some of the key ethical theories, principles and practice described by Dr Helen Kara at the National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) and watching an overview of Falmouth University’s approach to ‘Integrity, Research and Policy’ (Parker ca 2021).

There are various ethical approaches that can be taken:

Absolutist v Relativist

A concrete moral code of higher order principles applied to all research situations, as opposed to the perspective that a cost to research participants may be acceptable in order to achieve a greater good (Parker ca 2021).

Deontological v Consequentialist

A Deontological approach applies the intention of an act in order to determine its ethical goodness as opposed to the outcome of an act as the determining factor (Kara, 2017).

Virtue Ethics v Value Ethics

The perspective that the goodness of the individual is what drives ethical research as opposed to agreed collective morals and values leading to better research outcomes (Kara, 2017).

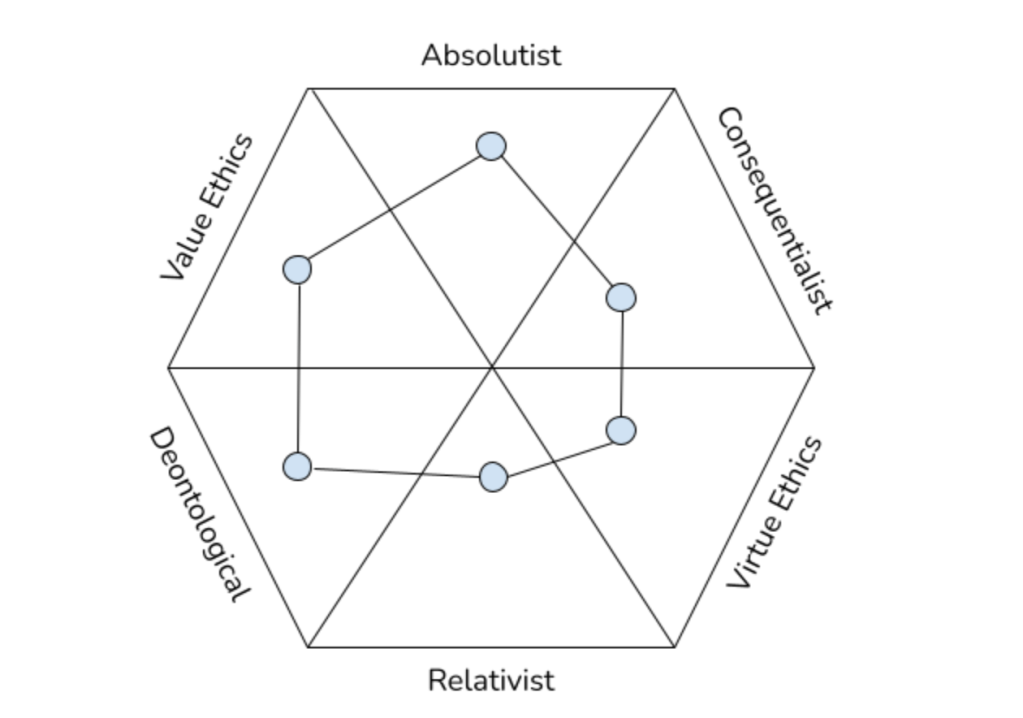

Although these are far from the only ethical theories – and not entirely in opposition to one another – as I considered each approach I decided to create a graphic to visually represent how I initially saw my view.

At first, I found myself leaning more towards an Absolutist way of thinking. I thought that to do deliberate harm of any kind to an individual would be untenable. Then I considered what we mean by harm. Is a doctor carrying out an operation doing temporary harm in order to reach a positive longer-term outcome? Is a sports coach pushing an athlete through a pain barrier? I next came to the realisation that in order to be comfortable with doing harm of any kind, it would have to be in prevention of a far greater harm; drawing parallels with Utilitarian philosophy. So great in fact, that I have a hard time imagining it. Hard, but not impossible, which perhaps means i’m not an Absolutist after all. Perhaps i’m actually a Relativist with a high threshold for what constitutes reward.

In the examples i’ve given above, the determining factor seems to be that of informed consent. The participant must agree that the return is significant enough to warrant the potential harm – and this consent is the cornerstone of what is considered to be ethical (Lazar et al, 2017).

In terms of how I will apply this learning to my future work, I will do so in the area of Game User Research (GUR).

Games User Research (GUR)

GUR is the umbrella term for the discipline which seeks to understand user behaviour, emotion and psychology in interactive media. It encompasses user evaluation strategies including usertesting and analytics (Mirza Babaei et al 2013).

The goal of this sort of research is to bring the project closer to the design vision. It aims to assess the success of the experience and review the responses of the player against the design intention and then utilise those learnings to inform further iterations of the design.

In the case of user testing, researchers seek to gain this understanding by collecting and analysing data from players interacting with a prototype or pre-released version of a game (IGDA ca 2021).

When I carry out user testing in upcoming course projects, it will be necessary to evaluate the risks and ensure that any research that has the potential to negatively impact on others is appropriately prepared for and mitigated.

On the face of it, it might not seem as though there is much to consider in the ethics of research in games. However, the ethical dilemmas that I may be faced in the field of GUR when working with human testers may be the same as in any other field of research, including; witholding information, deception or acts through gameplay that may diminish a participants self-esteem (Robson, 1993).

In addition, there are further ethical considerations I see in conducting researching for ideation in pre-production; especially if the game is focussed on a demographic characterised as vulnerable or a particular real-world place or community. It is important to understand the cultural implications and apply the correct ethical approach. For instance, in applying Indigenous vs Euro-Western ethical theory when carrying out research in partnership with Indigenous communities (Kara 2017).

Games have the potential to touch on extremely sensitive topics in interactive and immersive ways. This may include divisive political or social issues, violence or crime which may also be personally triggering for an individual. Potential for visceral reactions may be compounded further with with games and experiences built in VR (Behr et al. 2005).

Games also target a wide range of demographic groups which may often include children and people who are Neurodiverse. Other considerations may include those of culture, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation of testing participants and how that could impact on their experience. All of this must be carefully considered for risk of harm when I am developing my approach to research.

For each piece of GUR I undertake, I will assess it for risk in line with the Falmouth University Integrity and Ethics Policy. Once I have determined whether the project is Low, Medium or High Risk (Parker 2021). I will then create an action plan for review that meets the requirements of the risk level. For every piece of research I undertake involving people, regardless of risk level, I will ensure it is done with informed, and ongoing consent (Kara, 2017). I will also consider privacy and confidentiality, in terms of protection of the individual and operating within the law. For instance, when collecting and storing data in the UK I will need adhere to the constraints and requirements of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Further Research

It has been interesting to read more about the increasing amount of user testing undertaken using AI as we become increasingly better at imitating human cognitive processes, and the potential impact on GUR research ethics.

The cost v benefits of utilising AI and automation in this area are clear, particularly for small development teams where this is a very costly exercise (Moosajee and Mirza-Babei 2016). You can run thousands of level play-through tests in seconds in comparison with a human. Through my research, my conclusion is that at the moment a blended approach is most appropriate, with particular value in assessing mechanical aspects of the game like spatial navigation in level design in the early stages of development.

This perspective is supported by Stahlke and Mirza-Babaei in the concluding remarks of their paper, Usertesting Without the User: Opportunities and Challenges of an AI-Driven Approach in Games User Research:

‘AI techniques can thus improve the value, feasibility, and depth of the usertesting process by augmenting traditional approaches with computerized player models.’

(2018: 16)

In terms of the potential ethics challenges of research, AI might minimise the potential for player harm in GUR, but might also mask issues of inclusivity through developer bias. As long as human developers build the AI that carries out testing, they will build their own bias into that testing. I would suggest that this is in fact another argument – alongside the extensive business case – for building a diverse development team.

‘By breaking up workplace homogeneity, you can allow your employees to become more aware of their own potential biases — entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes.’

(Grant and Rock 2016)

This is something I already feel very strongly about and am interested to conduct further research on. I believe there may be a case to be made for diverse development teams writing better code, for all of the reasons that apply to business operations and innovation.

References

BEHR, Katharina Maria, Andreas NOSPER, Christoph KLIMMT and Tilo HARTMANN. 2005. ‘Some practical considerations of ethical issues in VR research’ Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 14 (6): 668–676. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/105474605775196535 [accessed 14 December 2021]

BENNETT, Christopher. 2010. What Is This Thing Called Ethics? 2nd ed. London: Routledge

CONSALVO, Mia. 2017. A Practical Guide for Doing Ethical Player Testing [Games Developers Conference]. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Q6MkcrpXYI [accessed 15 December 2021]

GAMES RESEARCH AND USER EXPERIENCE SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP. 2021. ‘What is a GUR/UX’. [online] Available at https://grux.org/what-is-gurux/ [accessed 14 December 2021]

GRANT, Heidi and David ROCK. 2016. ‘Why Diverse Teams are Smarter’ Harvard Business Review. [online] Available at: https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter [accessed 13 December 2021]

KARA, Helen. 2017. Research Ethics (Ethical Practice) [National Centre for Research Methods]. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R5vuihGRtyE [accessed 10 December 2021]

KARA, Helen. 2017. Research Ethics (Ethical Principles) [National Centre for Research Methods]. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKz1RmOnF7g [accessed 10 December 2021]

KARA, Helen. 2017. Research Ethics (Ethical Theories) [National Centre for Research Methods]. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyF8UzDMNsw [accessed 10 December 2021]

MIRZA-BABAEI, Pejman, Veronica ZAMMITTO, Joerg NIESENHAUS, Mirweis SANGIN, and Lennart E NACKE. 2013 ‘Games user research: practice, methods, and applications’. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: Extended Abstracts. Paris, France, 27 April – 2 May 2013. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262214587_Games_user_research_practice_methods_and_applications [accessed 17 December 2021]

MIRZA-BABAEI and Pejman and Naeem MOOSAJEE. 2016. Games user research (GUR) for indie studios. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (pp. 3159-3165). San Jose, California, USA 7 – 12 2016. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302074416_Games_User_Research_GUR_for_Indie_Studios [accessed 17 December 2021]

PARKER, Alcwyn. ca 2021. ‘Week 8: Integrity, Ethics and Policy’. Falmouth University [online]. Available at: https://learn.falmouth.ac.uk/courses/240/pages/week-8-integrity-ethics-and-policy?module_item_id=9190 [Accessed 10th November 2021].

STAHLKE, Samantha N and Pejman MIRZA-BABAEI. 2018. ‘Usertesting Without the User: Opportunities and Challenges of an AI-Driven Approach in Games User Research.’ Computers in Entertainment. 16 (2) 1-18. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.