This week’s topic is Rapid Ideation. The term Rapid Ideation refers to the development of a working prototype in a limited time.

Inspiration may be drawn from many places, including existing media where it may be remediated upon – inspired by and improved – or hypermediated upon – building on limited ideas through creative contradiction (Bolter and Grusin 1999). The outputs of a rapid ideation sprint may also take many forms including a Wireframe, Paper Prototype, Vertical or Horizontal Slice.

Game Design: Tools and Frameworks

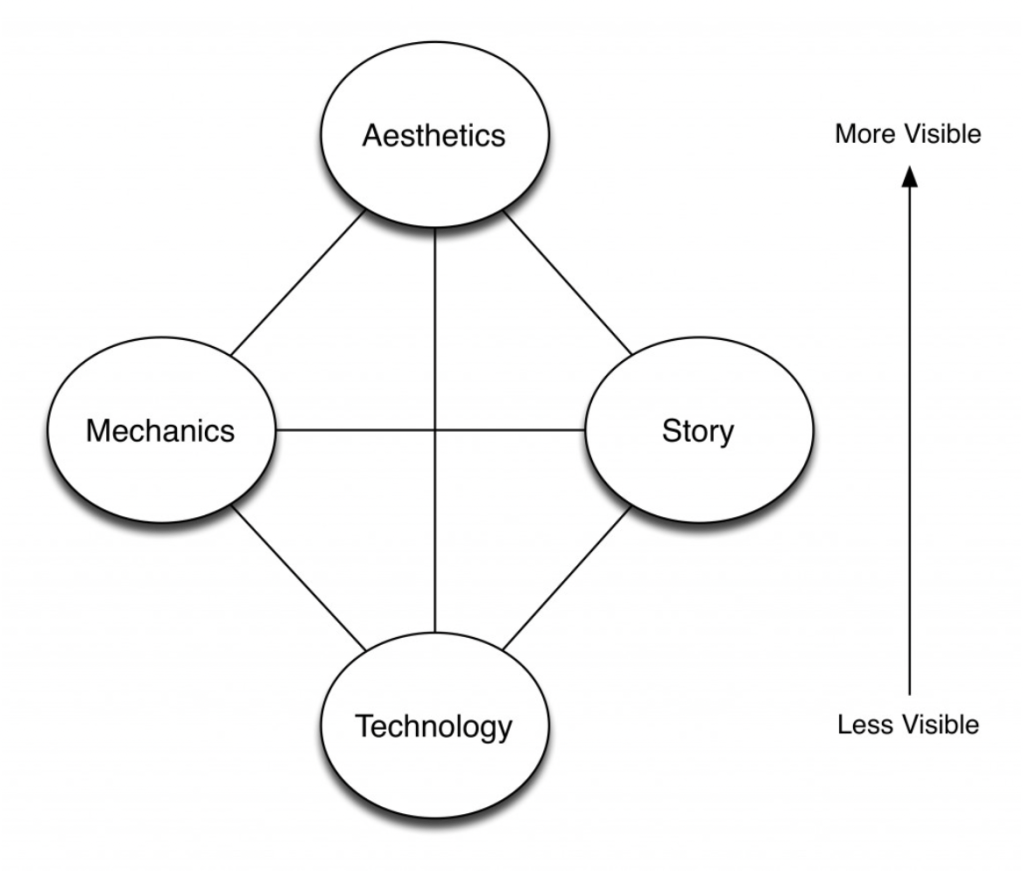

There are a range of tools that can be used to support ideation in game design and research including sketches and diagrams, paper prototyping, storyboards or user-driven prototypes. There are also some key game design frameworks that I have found useful in my ideation. The first is Jesse Schell’s Elemental Tetrad (2008) which splits game design into 4 key elements. Some of these elements are more visible to the player than others, but all must be considered and work together to support the design vision.

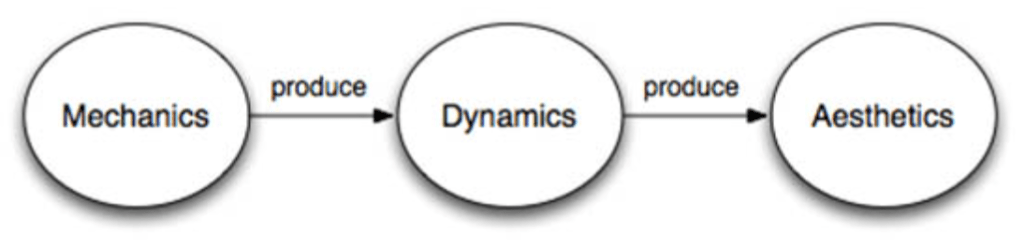

The second is MDA developed by Hunicke et al, which takes a similar approach, but focuses on the Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics of a project:

‘Mechanics describes the particular components of the game, at the level of data representation and algorithms. Dynamics describes the run-time behaviour of the mechanics acting on player inputs and each others outputs over time. Aesthetics describes the desirable emotional responses evoked in the player, when they interact with the game system’

(2004: 2)

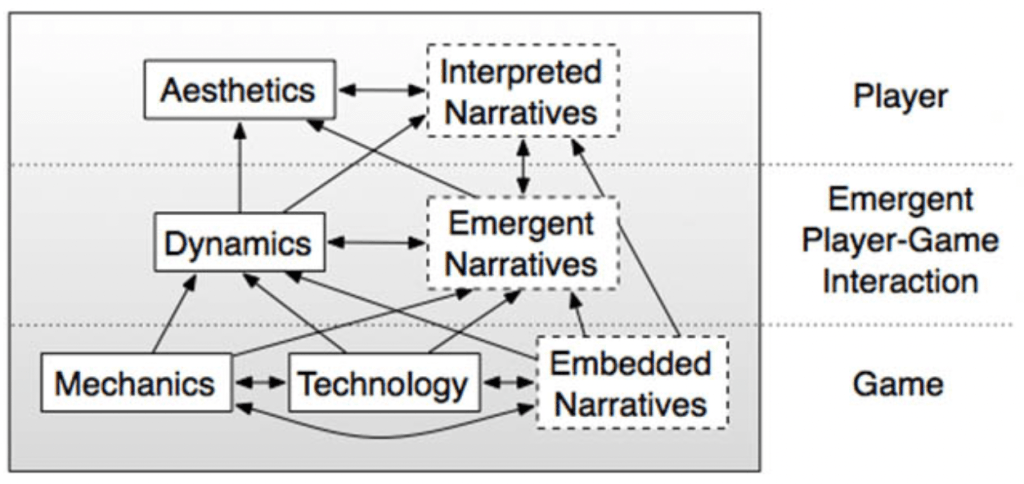

Ralph and Monu have further expanded on these frameworks to create MTDA+N, which includes a more nuanced breakdown of game narrative types which I have also found thought provoking. In particular, when considering what parts of a story the game itself will tell vs what will be told by player-game interaction and also the player themselves (2014).

Whatever the framework used as the foundation for ideation, there are 4 key components of prototyping and testing that warrant consideration:

- People – including those whom you are testing and the observers

- Objects – static and interactive, including the prototype and other objects the people and/or prototype interact/s with

- Location – places and environments

- Interactions – digital or physical, between people, objects and the location (Dam and Siang, 2020)

Failing to consider one or more of these elements in the ideation phase may mean that my prototypes are less successful or in need of more iteration cycles to achieve the desired outcome.

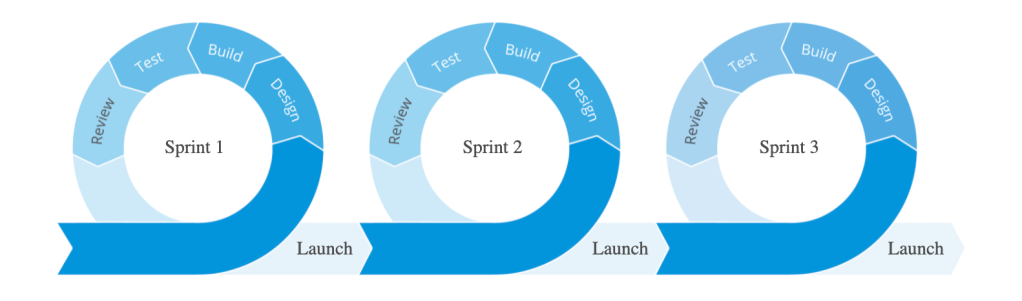

Once a prototype has been constructed, it will be important for me to swiftly move through cycles of testing and validation in order to make improvements. In rapid iteration, it is the goal to move through as many cycles as possible during the timeframe, which requires real focus. In the early stages, prototypes don’t need to be the finished article, just quick, rough and ready in order to validate specific concepts. My testing on the other hand, should be concise and efficient. Evaluation should focus on simple binary questions that allow for quick decision-making and improvements. This style of rapid iteration naturally supports Agile development and feedback loops, where these cycles are carried out in short, time-limited sprints.

A reflection I have made this week lies in understanding how a person’s typical thinking patterns can impact heavily on the quality of their ideation. As I learned during our creativity week, it is natural for humans to develop tried and tested thinking patterns and cognitive sets (Das, 2009). If the process of ideation is about creating new ideas, then it will be key to understand how my own knowledge and assumptions are formed in order to disrupt those thought patterns. Well-worn paths are less likely to lead to creative breakthroughs and it is important to challenge them.

I will apply learnings developed so far in critical reflection in an attempt to disrupt my thinking; in particular reflecting on the theories of “Reflexivity, Post-Modernism and Deconstructionism, and Critical Social Theory” in creating knowledge (Fook and Gardner, 2007: 23). Ideation tools can then be used to forge new paths and help me to create in new ways. For example, through considering this and undertaking a personality diagnostic with a mentor, I have realised that I usually form knowledge or draw ideas from the mind and am less influenced by the physical. Knowing this, I might now for instance use the technique of Bodystorming in a future project ideation session.

Bodystorming is the process of using an individual’s own body to physically experience a situation in order to ideate. It can involve role-play, simulation and constructed environments. Three examples of its application are:

- using the actual space or place in which the product you are designing will ultimately be used

- using a replicated, representative environment

- simulating a situation using actors

By placing yourself in the environment that the solution is meant for, it allows you to gain a different perspective than if you were only visualising. It supports empathy for the users and surfaces thinking specific to the environment. (Jones et al, 2010)

It also occurred to me that this was similar in approach to the development concept of dog fooding in software development; in that it is the practice of understanding how a solution will be used in the real world and using learnings gained to improve and ideate (Ash, 2003) .However, as Lydia Ash notes in her book this technique is not without its drawbacks:

‘In most projects the people consuming the dog food do not represent the people who will be using it, so they are blind to the usability problems.’

(2003: 17)

This challenge could also apply to the process of Bodystorming, in particular if you are ideating for a specific end-user; something I would be mindful of if I were to use this technique.

References

ASH, Lydia. 2003. The Web Testing Companion: The Insider’s Guide to Efficient and Effective Tests, Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing

BOLTER, Jay David and Richard Grusin. 1999. ‘Remediation: Understanding New Media’. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 4(4) 208-209. [online] Available at https://doi.org/10.1108/ccij.1999.4.4.208.1 [accessed 11th October 2021]

DAM, Rikke Friis and Teo Yu SIANG. 2020. ‘Prototyping: Learn Eight Common Methods and Best Practices’. Interaction Design Foundation [online]. Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/prototyping-learn-eight-common-methods-and-best-practices [accessed 13th October 2021]

DAS, Aniruddha. 2009. ‘Contextual Interactions in Visual Processing’. Encyclopaedia of Neuroscience. Elsevier [online]. Available at http://144.76.89.142:8081/science/article/pii/B9780080450469002096#! [accessed 2nd October 2021]

FOOK, Jan and Fiona GARDNER. 2007. Practicing Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

HUNICKE, Robin, Marc LEBLANC and Robert ZUBEK. 2004. ‘MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research‘ paper for the 2004 AAAI Workshop [online]. Available at: https://aaai.org/Library/Workshops/ws04-04.php [accessed 13th October 2021]

JONES, Peter, Oksana KACHUR and Dennis SCHLEICHER. 2010. ‘Bodystorming as Embodied Design’. ACM Interactions [online]. Available at: https://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/november-december-2010/bodystorming-as-embodied-designing1 [accessed 13th October 2021]

RALPH, Paul and Kafui MONU. 2014. ‘A Working Theory of Game Design: Mechanics, Technology, Dynamics, Aesthetics and Narratives.’ First Person Scholar [online]. Available at: http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/a-working-theory-of-game-design/ [accessed 13th October 2021]

SCHELL, Jesse. 2008. The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. Burlington MA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers

Full list of figures

Figure 1: Jesse SCHELL 2008. The Elemental Tetrad. From: SCHELL, Jesse. 2008. The Art of Game Design. CRC Press.

Figure 2: Robin HUNICKE, Marc LEBLANC and Robert ZUBEK The MDA Framework. From: Design and Game Research’. Available at: cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/pubs/MDA.pdf [accessed 13th October 2021]

Figure 3: Kafui MONU and Paul RALPH. 2014. MTDA+N Conceptual Framework. From: ‘A Working Theory of Game Design: Mechanics, Technology, Dynamics, Aesthetics and Narratives.’ First Person Scholar [online]. Available at: http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/a-working-theory-of-game-design/ [accessed 13th October 2021]

Figure 4: Maria DICESARE. 2021. Sprint Framework. From: Agile Process: Why You Need Feedback Loops Both During and After Sprints [online]. Available at: https://www.mendix.com/blog/agile-process-why-you-need-feedback-loops-both-during-and-after-sprints/ [accessed 13th October 2021]

You must be logged in to post a comment.