This week we explored the theme of creativity: how it fits into our thinking, our work, our lives and some of the tools we can use to spark it.

In my work, I most commonly use creativity to problem-solve. To support my personal goals, I completed a Linkedin Learning course Creativity at Work: A Short Course from Seth Godin. Godin states that ‘creativity at work is rooted in change’ (2021).

It is being open to ideas and trying things to see how they work on the understanding that they may not produce the intended outcome. A commitment to failure is necessary, as complex problems and creative projects are challenging by the very nature of their uniqueness. I have certainly seen and experienced the necessity for this commitment in my work. In fact, this is something I have adopted in all aspects of my life based on the theories and benefits of a Growth Mindset in learning. This theory asserts that ability is not fixed and that anything can be learned with effort. It places value in failure as a powerful part of learning; that the journey is as important as the outcome (Dweck 2006).

This theory also supports my research this week into creative thinking tools and techniques. Generating learnings from a creative process, connecting new thoughts and ideas are valuable in their own right, regardless of outcome. The journey to eventual success will involve many failures; and these should only be viewed as opportunities to learn. Creativity requires the thinker or artist to be bold, go down new, unexplored avenues and take those opportunities when they arise rather than be discouraged. This has emboldened me to take more risks in my practice going forward and attempt to make a game as soon as I am able to – despite my lack of programming experience.

Through my research this week I have also learned that as humans, there are many innate factors contributing to patterns of thinking which impede innovation.

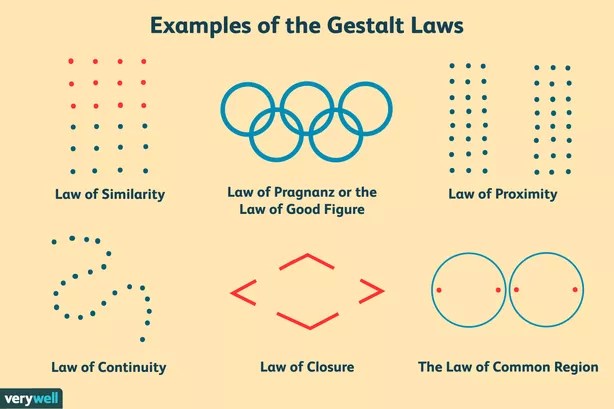

For instance; in cognition, human perception is far more complex than an individual passively receiving sensory signals. It may be affected and manipulated by their experiences, expectations and circumstances to create ‘Perceptual Sets’ (Weiten 2017: 121). Gestalt theory, originating in the work of Max Wertheimer, is focussed on how humans organise and perceive visual data to create the world around them and the relationship between objects (Giora et al 2012). Interestingly, I also made a mental link between this theory and that of Reflexivity in knowledge building and critical reflection; the creation of knowledge being influenced by the physical, social, emotional and intellectual factors that exist for the individual at the time of its creation (Fook and Gardner 2007).

Some of the key principles of the Gestalt theory of perception are as follows (Cherry 2021);

- Similarity: We will group items together that share visual elements like colour, size, or orientation.

- Prägnanz: We will perceive things in the simplest form possible. For instance, we interpret the olympic rings as overlapping circles as opposed to a set of curved lines (Dresp-Langley 2015).

- Proximity: We will usually view items that are physically near each other as a group (Ali and Peebles 2013).

- Continuity: We will perceive a relationship between items placed on a line or curve. Those that are not are perceived as separate.

- Closure: We will perceive items that form a closed object as a group and also mentally fill gaps that exist in order to organise and simplify them (Elder et al 2012).

- Common region: We tend to group objects together if they’re located in the same bounded area. This principle can actually override the others when items are placed in a boundary together, regardless of similarity etc (Elder et al 2012).

In addition, we place our attention selectively to filter out what our subconscious believes itself to be unimportant in a phenomena called ‘Inattentional Blindness’ (Weiten 2017 : 121).

This redundancy limits our perception and ability to spot unexpected value or learnings. It was demonstrated effectively in the results of the well-known Invisible Gorilla experiment, in which over half of participants watching a recording failed to see a person in a gorilla suit on screen because they had been tasked with counting the number of times a group of people passed a ball. I myself have experienced cognitive illusions such as this, for instance; searching my handbag for a wallet I believe to be red and completely missing the wallet in there that is actually black (Chabris and Simons 2010).

Similarly to the theories I have read associated with Critical Reflection, it is necessary to challenge our perception and assumptions in order to achieve deeper levels of knowledge and generate insights (Fook and Gardner 2007). A key learning here is that as a creative – although I may believe I am open to new mental pathways and unexpected discoveries – it will be necessary for me to use tools and techniques that disrupt these processes and my thinking. I have begun to explore this and applied two such techniques in this week’s challenge activity. I will continue to disrupt my thinking as the course progresses using these and other similar tools.

A useful model for applying these techniques in my creative process referenced in my research this week is that of ICEDIP (Petty, 2017). In this model, the creative process is described as having six phases:

- Inspiration: In which you research and generate many ideas

- Clarification: In which you focus on your goals

- Evaluation: In which you review your work and learn from it

- Distillation: In which you decide which of your ideas to work on

- Incubation: In which you leave the work alone

- Perspiration: In which you work determinedly on your best ideas

By working through these phases, I would be forced to explore my creative project in ways that might not necessarily come naturally to me. Personally, I see weaknesses in my own process in the evaluation phase and it is an area I would like to improve on through the program. This would also support my development in the distillation phase, which I also sometimes find challenging. I have a vivid imagination and whilst this makes the inspiration phase one of my strengths, I believe developing a process for evaluating those ideas would enable me to make better decisions about which ideas hold true value.

References

ALI, Nadia and David PEEBLES. 2013. ‘The effect of Gestalt laws of perceptual organization on the comprehension of three-variable bar and line graphs.’ Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. 2013;55(1) : 183-203. Sage Publications.

CHABRIS, Christopher and Daniel SIMONS. 2010. The Invisible Gorilla and other ways our intuition deceives us. [e-book] London: HarperCollins Publishers.

CHERRY, Kendra. 2021. ‘What Is Gestalt Psychology?’. Verywell Mind [online] Available at: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-gestalt-psychology-2795808 (Accessed 1st January 2022).

DRESP-LANGLEY, Birgitta. 2015. ‘Principles of perceptual grouping: Implications for image-guided surgery’. Frontiers in Psychology [online]. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01565/full [Accessed 1st January 2022].

DWECK, Carol. 2006. Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

ELDER, JH, M, KUBOVY and J WAGEMANS, et al.

ELDER, James H., Michael KUBOVY, Stephen E. PALMER, Mary A. PETERSON, Manish SINGH, Rüdiger VON DER HEYDT and Johan WAGEMANS. 2012. ‘A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure-ground organization.’ Psychology Bulletin. 2012;138(6) : 1172-1217. American Psychological Association.

FELDMAN Jacob, Sergei GEPHSTEIN , Ruth KIMCHI, James R. POMERANTZ, Peter A.VAN DER HELM, Cees VAN LEEUWEN.and Johan WAGEMANS. 2012. ‘A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: II. Conceptual and theoretical foundations.’ Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1218–1252. American Psychological Association.

GIORA, E, BF MARINO and S VEZZANI. 2012. ‘An early history of the Gestalt factors of organization. Perception, 41(2) : 148-67. Sage Publications.

GODIN, Seth. 2021. ‘Creativity at Work: A Short Course from Seth Godin’. Linkedin Learning [online]. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/learning/creativity-at-work-a-short-course-from-seth-godin/introduction-the-urgent-need-for-creativity?u=2120532 [accessed 3rd October 2021]

PETTY, Geoff. 2017. How To Be Better at… Creativity. 2nd edn. [e-book]. Raleigh: Lulu Enterprises Inc.

WEITEN, Wayne. 2017. Psychology Themes and Variations. Cengage.

Full list of figures

Figure 1: Creativity at Work: A Short Course from Seth Godin. Linkedin [screenshot by author]. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/learning/creativity-at-work-a-short-course-from-seth-godin/introduction-the-urgent-need-for-creativity?u=2120532 [Accessed 1st January 2022).

Figure 2: BEE, JR and VERYWELL. Examples of the Gestalt Laws [online]. Available at: https://www.verywellmind.com/gestalt-laws-of-perceptual-organization-2795835 9 [Accessed 1st January 2022).

Figure 3: CHABRIS, Christopher and Daniel SIMONS. 2010. Selective Attention Test [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo