I have never written in this format or style before, so to kick-off my work this year I decided to do some reading in order to develop my critical reflection skills.

I started with Practicing Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook by Jan Fook and Fiona Gardner.

In addition to providing useful tools and frameworks, it sets out the context for critical reflection and the academic theories the practice is based upon. The key learnings and theories that I intend to apply as I evaluate my progress are summarised below:

Knowledge is rarely binary. Whether something is true or false is often created by the individual according to a range of influencing factors. Knowledge is also rarely fixed. How it is created and interpreted varies depending on your personal state and situation. It is critical to be aware of these factors and how they can shape your thinking in order to truly understand it and achieve a deeper level of knowledge.

As described by Fook and Gardner, understanding the theories of ‘The reflective approach to theory and practice, Reflexivity, Post-Modernism and deconstructionism, and Critical social theory’ (2007: 23) will help me to be more aware of such factors and be critical of my own perspectives and conclusions.

The reflective approach to theory and practice rejects that knowledge can be constructed only through empirical means and encourages a learner to build their own experience and ways of knowing into building their professional practice. It also relates to our understanding of what constitutes legitimate knowledge and knowledge creation; examining how, where and when we have gathered that knowledge, the methods used to attain it, how this might have influenced the results and what it actually tells us (Fook and Gardner 2007).

Reflexivity is based on the understanding that our creation of knowledge is influenced by the physical, social, emotional and intellectual factors that exist for the individual at the time of its creation (Fook and Gardner 2007).

Postmodernism and deconstructionism relate to the challenging of a perceived single truth; in particular when that truth is the product of a linear, modernist development of knowledge (Fook and Gardner 2007). Postmodernism and deconstructionism examine the relationship that knowledge might have with the power of its proponents, challenging the purpose the knowledge may serve in preserving or strengthening that power and how hidden discourses might unknowingly influence our thinking (Healy 2000).

Lastly, Critical Social Theory focusses on the influence of social and political structures in the creation of knowledge and change. Again this theoretical tradition examines the dynamics of power, but from perspective of the cultural environment of the individual; and how they interpret and participate in it (Fook and Gardner 2007).

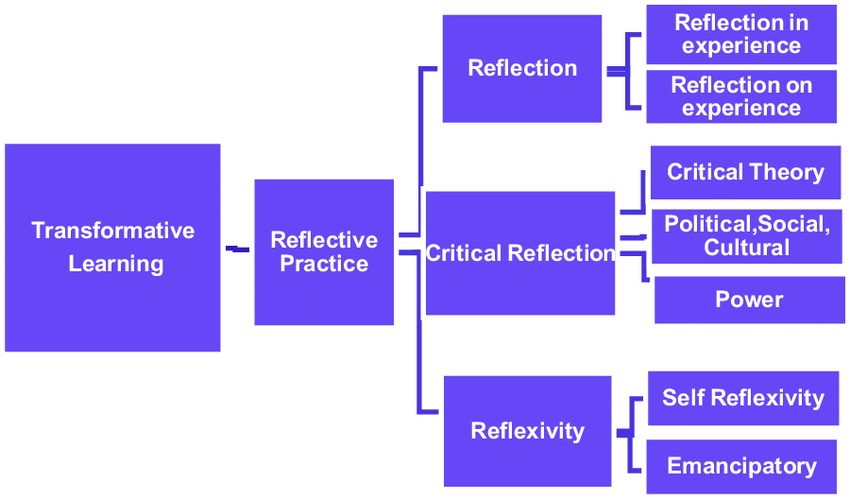

Actively evaluating my knowledge and assumptions – and challenging them as they develop – will undoubtedly lead to better outcomes and a transformative learning experience (Bass et al. 2017). I have already started to apply these theories to challenge my own world view. For instance, while conducting research for the week two topic of creativity I watched a Ted Talk given by David Kelley. In it he espoused the view that anyone can be creative given the right support and guidance (2012). This is aligned with my existing perspective and so I decided to challenge myself by watching a lecture given by Jordan Peterson – with whom I often disagree – with an open mind. In it he discusses creativity, intelligence and how these traits are ‘powerful determinants of innovation and general performance at complex tasks’ (2015).

Some additional professional learning also came from reflecting on the material. I made some interesting links between the contextual frameworks described and some of my experienced industry challenges.

Firstly, Fook and Gardner share some perspectives around how organisations respond to “uncertainty, risk and complexity” (2007: 7) and what those choices mean for those people within them. Fook and Gardner’s framework relates to delivering a series of workshops to professionals delivering “human service work” (2007: 7): doctors, social workers or teachers for instance.

Whilst it is not strictly speaking a ‘human service’ discipline, there are many parallels within Developer Relations Management (DRM). It is by and large a human-to-human service, based on delivery of value which is often vague in scope and difficult to measure. The described “tension that is created between value-based professional practice and economically and technically focussed organisations” (Fook anad Gardner 2007: 9) helped me to understand some of the challenges of working in the discipline in a private company.

In order to build a repeatable, scalable business I have sought ways to quantify value delivered, other than by measuring customer satisfaction. I have been pursuing this, not only for ourselves to assess performance, but also to support those that purchase our services in assessing the return on their investment. As a bespoke, value-based service, this is incredibly difficult to achieve. This section of the book helped me to reflect on and better understand that challenge.

I also recognised that in my role leading a team in this discipline I had responded to the challenges of working in a human, value-based environment in many of the ways described: working to rules and procedures, generating paperwork, focus on the parts rather than the whole: narrowing or limiting service delivery and a focus on outcomes (Fook and Gardner 2007). This has given me some food for thought in terms of how these responses may have influenced those on my team and how I might better support them.

Lastly, I have made some interesting personal discoveries while reading this book.

I have realised that I often mentally position people at work as either an ally or antagonist in a very binary way, depending on how I perceive their conduct. I will now be consciously looking for and questioning this, on the basis that the truth I have constructed will be influenced by my own circumstances and without understanding of the whole picture of that person’s experience.

Furthermore, I sometimes struggle with feelings of being a professional or intellectual imposter. I believe this is rooted in the fact that I have followed a non-academic career path to my current role, which is less usual among my peers and friends. While reading the segment on Reflexivity, I learned this theory asserts that knowledge isn’t something that exists outside, or separately, from our own experiences and sense of self.

My imposter feelings tend to surface from situations where I believe another person to be more qualified. I realised that I have always had an assumption that knowledge is rooted in knowing through learnings given to you by somebody else more experienced; developed in a traditional, modernist way. In these cases, I assume that they have true knowledge whilst I do not, because mine is experiential or self-taught. I have more confidence in knowledge deemed worthy by someone else more traditionally qualified. I have realised that I have held a hidden belief that the knowledge I have developed is somehow less valuable because it is only based on my ability to judge its value. It is my hope that as I continue to learn to critically reflect I can continue to build confidence, surface more underlying assumptions and challenge these ways of thinking.

References

FOOK, Jan and Fiona GARDNER. 2007. Practising Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

HEALY, Karen. 2000. Social Work Practices: Contemporary Perspectives on Change. London: Sage.

KELLEY, David. 2012. ‘How to Build Your Creative Confidence’ [Ted Talk]. Youtube [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=16p9YRF0l-g [accessed September 20th 2021].

PETERSON, Jordan B. 2015 ‘Personality Lecture 18: Openness – Creativity & Intelligence’ [seminar recording]. Youtube [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6rm0LrO9vU [accessed September 20th 2021].

Full list of figures

Figure 1: Jan FOOK and Fiona GARDNER. 2007. Practising Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook: A Handbook. [online] Available at https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=zOZRwQ8I5gUC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false [accessed 22nd December 2021].

Figure 2: Janice BASS, Jennifer FENWICK and Mary SIDEBOTHAM. 2017. Development of a Model of Holistic Reflection to facilitate transformative learning in student midwives. [online] Available at https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Conceptual-framework-underpinning-the-Holistic-Reflection-Model_fig3_315733251 [accessed 22nd December 2021]

Figure 3: INNERSLOTH. 2018. Among Us. [online] Available at https://www.sportskeeda.com/esports/best-among-us-settings-solo-imposter-games [accessed 22nd December 2021]